Slieve Aughty History

Slieve Aughty History

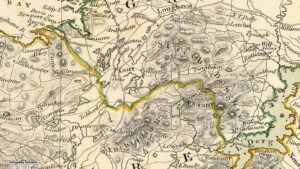

The Sliabh Aughty hills contain vast tracts of some of the most desolate landscapes in Ireland. The mountains are often referred to by their Gaelic name Sliabh Echtge. The Lady Echtge, granddaughter to Finde, one of the Tuatha de Danann gave her name to these hills. She married Fergus MacRuairi, who held those hills and mountains by his right of cupbearer to the King of Connacht. He bestowed the mountain valleys to Echtge to feed the cows, which she brought with her as her dowry. Two of these cows had been previously remarkable for their fruitfulness and great flow of milk and were placed one each side of the river which divide the fertile land from barren land. Hence the river has been called “Abhainn dá Loilgheach” – the river of the two milch cows. The less fortunate animal naturally reduced her milk flow. This river flows from the Derrybrien mountains to Lough Cutra.

The hills extend from our own parish of Kilchreest to the Shannon and offer some spectacular scenery. The chief rock formations are silex, though other ones particularly limestone are found. Many people still speak of coal and slate being found on the Roxboro mountain.

MacLonan sang the praises of the Aughty mountains in a long poem of 132 lines beginning – ‘Delightful, delightful, lofty Echtge’.

He mentions the hills, villages, fords, rivers, lakes, woods, etc. and he also gives an account of the many tribes and warriors who inhabited or hunted on these mountains including Fionn Mac Cumhaill. In the Annal of the Four Masters, it is recorded that Mac Lonan died in 892 A.D.

The mountains also provided inspiration for some of the poetry of Yeats and it is impossible to estimate their influence on the writings of Lady Gregory. One of her best plays “The Gaol Gate” is set against the background of a mountain village. The wild lonesome call of the mountain is found in the music of some of the greatest exponents of traditional music like Joe Burke and Joe Cooley.

As one travels along the mountain roads on a winter evening one cannot but be affected by a deep and abiding sense of the past. Here and there are scattered ruins of whole villages and isolated houses and the abandoned schools that remind us of the many families who worked their small holdings and cut their turf on the many bogs in the valleys between the mountains. Alas, the landscape is changing all too fast as the Forestry Department drain and plant. How many people in Sydney, Philadelphia, London and elsewhere can trace their roots to these isolated mountain valleys. Many Sliabh Aughty emigrants did well in their adopted lands. The story of the Durack family is recounted in the classic Australian historical work “Kings and Grass Castles”. The Duracks employed many Sliabh Aughty emigrants in their farming empire.

Dr. Fahy, writing around 1890, mentions the many ruins of the houses of the former industrious poor. So it seems that in the early 19th century the population in the mountain valleys must have been very high. The famine wiped out many families. Today Sliabh Aughty is more desolate than ever and there was a massive exodus when families got holdings on the Roxboro estate after 1927.

On the north slope of the Roxboro mountains the rhododendrons in full bloom in June are a beautiful sight. Deer were once plentiful on the mountains but after becoming almost extinct are now returning in great numbers.The highest point in the Aughty mountains is Cashlaundrumlahan and the highest point in the parish is Scalp.

Sruthán na bhFíonn-The Winestream

This stream, located in Gortnamanagh is mentioned in the Kilchreest N.S. Folklore Collection. According to the folklore account the stream changes into wine on the 6th of January each year when the clocks strike twelve at midnight.

Coill Buidheen

This area, situated in Gortnamanagh, is named after St. Buidheen. According to folklore the saint had a gamble line through the mountain from Co. Clare to Roxborough. It is also said that he built a leachtán (pile of stones) and placed a cross in the centre which was venerated for many years. There is a tradition that people visited the cross in times of trouble.

The Soldier’s Bridge

This bridge is one of three famous bridges in the parish of Kilchreest- the other two are the Seven Eye Bridge at Kilaspic and the Volunteer Memorial Bridge at Roxborough. All three span the Roxborough River which connects Roxborough and Coole – the two places central to the life of Lady Gregory. According to folklore this bridge is named after a local man named O’Loughlin who served with distinction in the British Army. The people who lived south of the river had to cross it by using stepping stones before the bridge was built.

Gort na Manach – Gortnamanagh – The Monks’ Tillage Field.

Gortnamanagh is divided into two separate townlands – Gortnamanagh East (413 acres) and Gortnamanagh West (426 acres). It is situated in the parish of Kilchreest in the barony of Loughrea in the foothills of the Sliabh Aughty Mountains. The whole area is steeped in history and folklore. Joe Cormican, a local man who worked for the Irish Folklore Commission in the late 1930’s, collected a wealth of material in this area. The Tithe Applotment books of 1829 recorded Patrick Hawkins, Sarah Lynch and Robert Power as tithe payers in Gortnamanagh East. Robert Power owned Gortnamanagh East and he purchased Gortnamanagh West through the Encumbered Estates Court in 1851. Folklore claims that Gortnamanagh did not lose any house during The Great Famine but population statistics do not support this claim. Between 1841 and 1851 the number of houses in Gortnamanagh East declined from 25 to 14 while the population dropped from 157 to 73 – a 54% decline. In the same decade the number of dwellings in Gortnamanagh West declined from 10 to 8 while the population reduced from 57 to 37 – a 35% decline. Griffiths’ Valuation of 1856 records Patrick Hawkins, Stephen Hawkins, John Walsh, Patrick Deely, Martin Deely , John Lally Francis Carty, William Carty and Mary Carty as householders in Gortnamanagh East.

This primary source also records a schoolhouse here and folklore strongly supports the existence of a hedge school here.

Householders in Gortnamanagh West included Bartholomew Buckley, John Dooley and Martin Lally. Robert Power held a position as Recorder for Galway and he was a benevolent landlord.

Raftery, the poet often visited Gortnamanagh in his travels around South Galway in the early 19th century and his attendance at a wake is the subject of an amusing story in Joe Cormican’s Collection.